After I read an article on insidehighered.com, I wondered about the state of the Socratic method in American classrooms. The article chronicles the case of Professor Steven Maranville at Utah Valley University. He teaches a capstone business course and his style is to ask questions even if students don't volunteer to answer.

It seems that students complained about that (and pedagogical choices) and that those complaints contributed to the university denying him tenure.

I won't attempt to judge his employment status or his classroom teaching, but the article points to other cases where the power of student evaluations and opinions on faculty rehiring was significant. Professors at Louisiana State University and at Norfolk State University are noted. I also noticed a number of online posts recently about an article headlined "NYU Prof Vows Never to Probe Cheating Again—and Faces a Backlash."

Maranville's style of pedadgogy is described as Socratic, "engaged learning" in which he "pushed for students to go beyond lectures" and created teams for assignments outside class. I don't hear anything very radical in any of that. If done well, it sounds quite admirable.

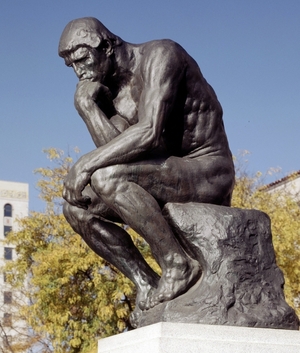

The Socratic Method as a style of teaching is named after the classical Greek philosopher Socrates who used this method of inquiry. It is covered in chapter one of the textbook I use in my critical thinking course, and I can't really imagine teaching a class face-to-face or online without using some form of this questioning technique.

This kind of inquiry and debate between individuals is popular in law schools and probably used more in the humanities and the social sciences. Using opposing viewpoints and asking and answering questions stimulates critical thinking and often illuminate ideas.

It is a dialectical method, and so it can often generate oppositional discussion and the defense of one point of view is up against the defense of another. I suppose that opposition can, if the discussion lacks discipline, lead to out and out arguing.

Maybe the Socratic method seems negative because it uses a method of hypothesis elimination. The stronger hypotheses are found by identifying and eliminating those that lead to contradictions or that cannot be defended.

As the article points out, one advantage of this kind of teaching is that it challenges students "to learn how to think on their feet." In general, I find that students at the undergraduate and graduate level don't like that challenge, especially if they have been not been asked to do it in other classes.

It wasn't Socratic teaching that got the NYU prof mentioned above in trouble. It was his attempt to be more aggressive about cheating and plagiarism in his introductory information technology class. Perhaps feeling safer because he had tenure, he decided to use the Blackboard course-management system and Turnitin's plagiarism-detection software together for the first time. Those integrated software packages allows assignments that are submitted to be automatically checked for matches to materials online.

He found that plagiarism was "pervasive" and 22 of the 108 students admitted cheating by the end of the semester.

The connections to the earlier Socratic case? Students, especially those in certain majors, are simply not asked to do much writing. (It is one of the reasons the Writing Initiative at PCCC was launched.) And faculty in those disciplines often feel unprepared to evaluate writing "as writing" as opposed to grading based on subject matter content. Students have not been asked to do this kind of writing, and instructors are not prepared or unwilling to "police" writing for plagiarism.

Introduce some powerful software that detects it automatically, even on papers or students that you would not have suspected, and an ugly truth is revealed.

Of course, the other connection in these two cases is that the teachers paid for their actions with bad student reviews. Professor Ipeirotis dropped to a below-average score of 5.3 (of 7.0) from his usual 6.0 to 6.5. He claims that "The Dean’s office and my chair ‘expressed their appreciation’ for me chasing such cases (in December), but six months later, when I received my annual evaluation, my yearly salary increase was the lowest ever, and significantly lower than inflation, as my teaching evaluations took a hit this year."

As anyone who has pursued an academic integrity case at a college with the administration probably discovered, it can take up many hours away from your actual teaching or research. Sadly, when he posted on a blog that he had decided to no longer pursue cheating instances, that too was met with a backlash.

Lesson learned? Well, I completely agree with what he says: "Rather than police plagiarism, professors should design assignments that cannot be plagiarized." I am actually presenting tomorrow at a writing across the curriculum faculty roundtable here at PCCC on just that topic. I hope to get a positive response from faculty, and will report back here soon.

This is a cross-posting from my blog at Serendipity35.net