|

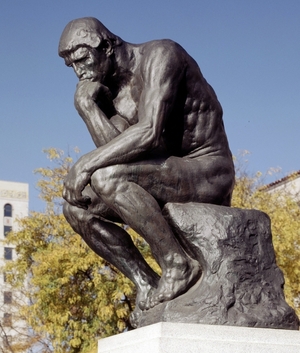

| Rodin's The Thinker, doing some System 2, slow, deliberative thinking. |

In 2002, Daniel Kahneman won a Nobel Prize in economics. But he isn't an economist. He won it for work in psychology that challenged the rational model of judgment and decision-making. He is considered one of our most important thinkers and his ideas have had an impact on economics, medicine, and politics.

His newest book is Thinking, Fast and Slow

His newest book is Thinking, Fast and SlowIn a simplified explanation, System 1 is the fast, intuitive, and emotional system. System 2 is slower, more deliberative, and more logical.

Both are necessary and Kahneman shows both the capabilities and benefits, and the faults and biases of them.

Perhaps the part that most interested me is that he has found a type of thought that's actually not very compatible with the way we think: decision-making. Decision-making is a chapter in every book about critical thinking.

"We have a very narrow view of what is going on," Kahneman says. "We don't see very far in the future, we are very focused on one idea at a time, one problem at a time, and all these are incompatible with rationality as economic theory assumes it."

In an interview, he said that an example of System 1 thinking would be the response to hearing a male voice say, "I believe I am pregnant." That would be an example of very fast System 1 thinking. Kahneman says, "It's the same process of recognizing things and distinguishing the familiar from the unfamiliar. You're coming up with solutions that have worked in the past, that's what's called expert intuition."

But if you are asked to multiply 87 by 14 in your head, System 2 takes over.

Here's an excerpt from the book:

When you are asked what you are thinking about, you can normally answer. You believe you know what goes on in your mind, which often consists of one conscious thought leading in an orderly way to another. But that is not the only way the mind works, nor indeed is that the typical way. Most impressions and thoughts arise in your conscious experience without your knowing how they got there. You cannot trace how you came to the belief that there is a lamp on the desk in front of you, or how you detected a hint of irritation in your spouse's voice on the telephone, or how you managed to avoid a threat on the road before you became consciously aware of it. The mental work that produces impressions, intuitions, and many decisions goes on in silence in our mind.

System 1 activity is completely unconscious, automatic and very quick. "You're surprised by something, but you don't really know what surprised you; you recognize someone, but you don't really know what cues cause you to recognize that person," he states.

System 2 activity is orderly computations, rules and reasoning. It is also the system that (luckily for us) is monitoring thoughts, actions and speech so that we don't always say everything that comes to mind.

Kahneman's two systems are an interesting approach to thinking and decision-making. But he recognizes that they are just language to explain concepts and don't actually exist in our brains.

My students might then ask, "So why study about them?"

"Clearly, the decision-making that we rely on in society is fallible," Kahneman says. "It's highly fallible, and we should know that." We should know it because knowing gives us the ability to do something about it.

No comments:

Post a Comment