|

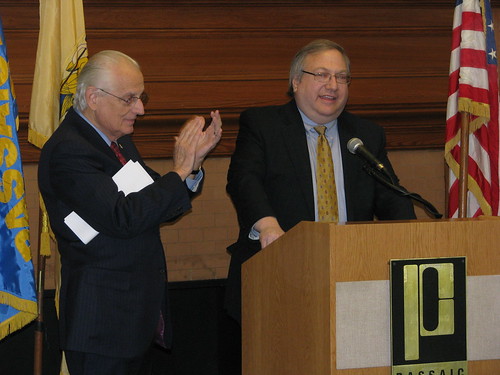

| Representative Bill Pascrell (left) and Dr. Rose at Passaic County Community College |

Last month, U.S. Represetative Bill Pascrell, Jr. (D-NJ-08) announced that Passaic County Community College (PCCC) has been awarded a new grant through the Department of Education’s Developing Hispanic Serving Institutions (HSI) Program.

The first year of the grant awards $541,813 to the College and the department anticipates a similar grant being given to the college annually for the next five years.

The Hispanic-Serving Institutions Program provides grants to assist HSIs to expand educational opportunities for, and improve the attainment of, Hispanic students. The HSI Program grants also enable HSIs to expand and enhance their academic offerings, program quality, and institutional stability.

The current Writing Initiative that began in 2007 and ends September 30, 2012 is part of the same DOE Title V program.

“PCCC put together a fantastic proposal and I am pleased that the federal government is seeing fit to support our community college here in Paterson ,” stated Pascrell, a former educator who led a grassroots movement to make sure the college was founded in Paterson . “Building strong skills in math, reading and writing are central to our students’ pursuit of educational excellence and advancement. I applaud PCCC for its focus on our student’s classroom performance, and working to secure resources that will improve academic achievement right here in Passaic County.” Pascrell served on the Board of Trustees at PCCC and gave the commencement address at the college this Spring.

PCCC will invest the grant into a comprehensive five year reform effort that seeks to increase achievement of Hispanic and other low-income students by improving course pass rates and persistence rates of college-level students enrolled in several barrier or “gatekeeper” courses.

“Our highest priority at Passaic County Community College is to ensure that our students meet their goals,” said Dr. Steven Rose, the President of Passaic County Community College. “These resources will allow us to implement innovative programs and services to better support our students. Again, we thank Congressman Pascrell for his ongoing four-decade commitment to the College.”